PatentNext Summary: Artificial Intelligence

(AI) typically involves certain common aspects such as training

data and AI models trained from that training data. Nonetheless, a

recent Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) decision found that it

is not always obvious to combine these common aspects to render an

AI-based medical device invention unpatentable.

****

Artificial Intelligence (AI) typically involves certain common

aspects. This includes, for example, training data, AI training

algorithm(s) that use the training data to train an AI model, and

predictions and/or classifications as output from the trained AI

model.

Could a person of ordinary skill in the art (e.g., a computer

scientist) find it obvious to combine these common aspects to

arrive at any given AI-based invention?

The Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) recently answered

“no” to this question in Intel Corp. v. Health

Discovery Corp., IPR2021-00552, Final Written Decision, Paper

No. 38 (September 12, 2022).

Patent-at-Issue

Intel Corp. (“Intel”) had filed a petition to

institute an inter partes review (IPR) of U.S. Patent 7,542,959

(the “‘959 patent”).

As an overview, the ‘959 patent describes an AI-related and

medical device-related invention that uses Support Vector Machines

(SVM) and Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) for selecting genes

capable of accurately distinguishing between medical

conditions.

Generally, an SVM is a known type of AI algorithm that finds a

“hyperplane” (i.e., a boundary) that distinctly

classifies mapped training data. RFE is a known type of AI

algorithm used to select features (columns) in a training dataset

that have an impact on an output prediction or classification.

The ‘959 patent describes the identification of a

determinative subset of features within a large set of features.

Such identification is performed by training the SVM to rank the

features according to classifier weights and where features are

removed to determine how their removal affects the value of the

classifier weights. Id. “The features having the

smallest weight values are removed, and a new support vector

machine is trained with the remaining weights.” ‘959

Patent, Abstract. “The process is repeated until a relatively

small subset of features remain that is capable of accurately

separating the data into different patterns or classes.”

Id.

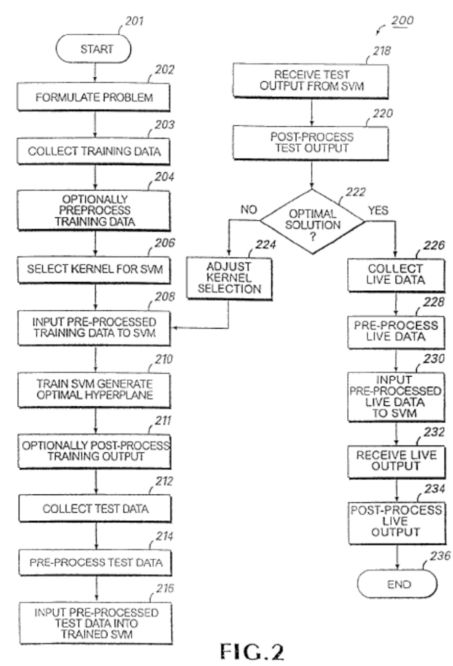

Figure 2 shows a flowchart for using a support vector machine

(SVM) in accordance with the ‘959 patent.

As shown in Figure 2, the SVM is trained using training data to

generate an optimal hyperplane. ‘959 Patent at 16:51-17:4. Test

data is input into the trained SVM “to determine whether the

SVM was trained in a desirable manner.” Id. at

17:11-13. If not, the kernel selection is adjusted at step 224, and

the training process is repeated from step 208. Id. at

16:47-57. After the optimal kernel is selected, the SVM is further

optimized through feature selection to reduce the dimensionality of

feature space. See id. at 26:20-33.

The ‘959 patent uses RFE, where the feature corresponding to

the smallest weight in the new classifier is eliminated, and at

each iteration, a new classifier is trained with the remaining

features. Id. at 52:52-64.

Claim 1, which is representative claims-at-issue, and that

recites an SVM (“support vector machine” (bolded)), is

reproduced below.

A computer-implemented method for predicting patterns in

biological data, wherein the data comprises a large set of features

that describe the data and a sample set from which the biological

data is obtained is much smaller than the large set of features,

the method comprising:

identifying a determinative

subset of features that are most correlated to the patterns

comprising:

(a) inputting the data into a

computer processor programmed for executing support vector machine

classifiers;

(b) training a support

vector machine classifier with a training data set

comprising at least a portion of the sample set and having known

outcomes with respect to the patterns, wherein the classifier

comprises weights having weight values that correspond to the

features in the data set and removal of a subset of features

affects the weight values;

(c) ranking the features

according to their corresponding weight values;

(d) removing one or more features

corresponding to the smallest weight values;

(e) training a new classifier

with the remaining features;

(f) repeating steps (c) through

(e) for a plurality of iterations until a final subset having a

pre-determined number of features remains; and

generating at a printer or

display device a report comprising a listing of the features in the

final subset, wherein the final subset comprises the determinative

subset of features for determining biological characteristics of

the sample set.

Petitioner’s Grounds and Prior art

The Petitioner asserted two grounds of invalidity, both pursuant

to Section 103.

The two grounds each relied on three prior art references that

together taught all of the claim elements of the ‘959

patent:

Kohavi: Kohavi teaches a feature subset

selection method for selecting a relevant subset of features upon

which to focus a learning algorithm’s attention while ignoring

the rest. See Kohavi et al., “Wrappers for Feature

Subset Selection,” Artificial Intelligence 97, 273-324

(1997).

Boser: Boser teaches a “pattern

recognition system using support vectors”- i.e., an SVM. US

Patent No. 5,649,068, July 15, 1997, to Boser et al.

Hocking: Hocking teaches an iterative process

that removes variables based on weight-vector ranking until a

subset that provides the best regression is identified.

See Hocking et al., “Selection of the Best

Subset in Regression Analysis,” Technometrics, 9:4, 531-540

(1967).

In particular, Petitioner had argued that skilled artisans would

have been motivated to combine elements of these prior art

references to arrive at the claimed invention.

PTAB’s finding of No Motivation to

Combine

Even though the prior art references taught all elements, the

PTAB held that the Petitioner failed to show that a skilled artisan

would have combined the prior art in the manner cited by the

‘959 patent’s claimed invention.

The PTAB based its decision on Personal Web Techs., LLC v.

Apple, Inc., 848 F.3d 987, 993 (Fed. Cir. 2017), where the

Federal Circuit had found that even though a skilled artisan

may have understood that a set of prior

art references could be combined in a

specific claimed manner, it is not enough; instead, it must be

shown a skilled artisan would have known

to pick out the set of prior art references and combine them to

arrive at the claimed invention. IPR2021-00552, Final

Written Decision at 31.

The PTAB had agreed with the Petitioner that the prior art

references could be combined.

However, the PTAB found that the Petitioner had nonetheless

failed to provide sufficient evidence showing that a skilled

artisan would have been motivated to do

so

[W]e are not persuaded by Petitioner’s evidence and

contention that a skilled artisan would have had a motivation to

modify Kohavi’s wrapper method to rank the SVM features

according to their corresponding weight values as [recited by the

claims].

Intel Corp., IPR2021-00552, Final Written Decision at

26-27.

In particular, the PTAB found that the Petitioner’s evidence

and reasoning demonstrated “nothing more than a skilled

artisan, once presented with the separate pieces of highlighted

information in Kohavi, Boser, and Hocking, may have understood that

they could be combined in the manner claimed.” Id. at

27.

As to the specific AI technical features, the PTAB found that no

motivation was demonstrated “to modify Kohavi’s wrapper

method by changing the ranking used in

the feature subset selection algorithm

from an estimation of the performance of

an induction algorithm to classify data properly to a

variable–feature weight–used in the algorithm of an SVM to

classify data.” Id.

In particular, even though all elements of the claims-at-issue

were found in the prior art and where a skilled artisan may have

understood that such elements could have

been combined, the PTAB found that there was no evidence provided

that showed that a skilled artisan would

have made the combination as claimed by the ‘959 patent. At

most, “the combined Kohavi/Boser/Hocking disclosures suggest

that a skilled artisan, once presented with the separate pieces of

highlighted information from those references, may have understood

that they could be combined in the manner claimed, but that is not

enough because Petitioner has not shown persuasively why a skilled

artisan would have known to pick out those three references and

combine them to arrive at the claimed invention.” Id.

at 31 (citing Personal Web Techs., LLC v. Apple, Inc., 848

F.3d 987, 993 (Fed. Cir. 2017)).

Dissenting Opinion

It should be noted, however, that the decision was split 2-to-1,

where Judge Garth D. Baer broke from the majority in dissent.

Judge Baer argued that “Petitioner explained, with support

from its expert . that its proposed addition of Hocking’s

vector weight ranking criteria ‘applies a known technique

(Hocking’s variable selection) to a known device (Kohavi’s

RFE method using Boser’s SVM) which is ready for improvement to

yield predictable results.’ ” Intel Corp.,

IPR2021-00552, Final Written Decision at 41-42 (citing KSR

Int’l Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 550 U.S. 398, 417 (2007)).

Because of this, Judge Baer agreed that the claimed invention

‘959 was nothing more than an obvious combination of known

techniques applied to a known device, yielding only predictable

results and thus obvious under KSR’s framework. Id. at

42.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.

Source: https://news.google.com/__i/rss/rd/articles/CBMifWh0dHBzOi8vd3d3Lm1vbmRhcS5jb20vdW5pdGVkc3RhdGVzL3BhdGVudC8xMjU2MTc4L3B0YWItZmluZHMtYXJ0aWZpY2lhbC1pbnRlbGxpZ2VuY2UtYWktbWVkaWNhbC1kZXZpY2UtcGF0ZW50LW5vdC1zby1vYnZpb3Vz0gEA?oc=5